Hearing Loss

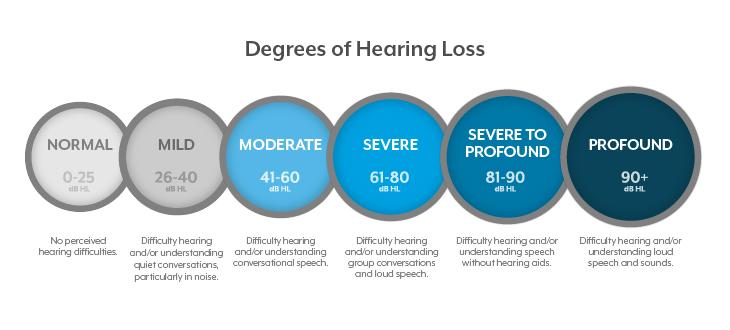

A person is considered to have hearing loss if their ability to hear is not on par with that of someone with normal hearing, defined by hearing thresholds of 20 dB or better in both ears. Hearing loss can manifest in various degrees, ranging from mild to profound, and may affect one or both ears. Primary causes of hearing impairment include congenital or early onset childhood hearing loss, persistent middle ear infections, damage from prolonged exposure to loud noises, age-related hearing decline, and the use of ototoxic drugs that harm the inner ear.

HEARING LOSS CHARACTERISTICS

Hearing loss is characterized by several important factors that significantly impact audiological rehabilitation. The degree and configuration of hearing loss play a crucial role in understanding a person's hearing sensitivity. The audiogram, a graphical representation of hearing abilities across frequencies, displays different configurations such as flat, sloping, and precipitous patterns. The degree of hearing loss is a key determinant, ranging from mild to profound, influencing the choice of rehabilitation strategies.

The time of onset and type of hearing loss are additional critical aspects. Prelingual deafness occurs at birth or before speech development, potentially impacting language acquisition during crucial early years. Perilingual deafness refers to acquiring deafness while developing the first language, while postlingual deafness occurs after age 5, affecting speech and education to varying degrees. Sudden hearing loss, characterized by an abrupt partial or complete loss within 72 hours, presents unique challenges in rehabilitation. Progressive hearing loss, developing gradually or worsening over time, poses difficulties in identifying changes in hearing abilities.

Audiological rehabilitation strategies must consider the individual's auditory speech recognition ability. Factors like the time of onset and degree of hearing loss influence the extent to which normal speech and language skills are preserved. Recognizing these characteristics helps tailor rehabilitation interventions, encompassing communication strategies, hearing aids, cochlear implants, and assistive devices. The goal is to enhance overall communication abilities and improve the individual's quality of life.

In summary, understanding the degree, configuration, time of onset, and type of hearing loss is vital in formulating effective audiological rehabilitation plans. These factors guide professionals in selecting appropriate interventions to address the unique needs of individuals with hearing impairment, ensuring comprehensive support for their communication and language development.

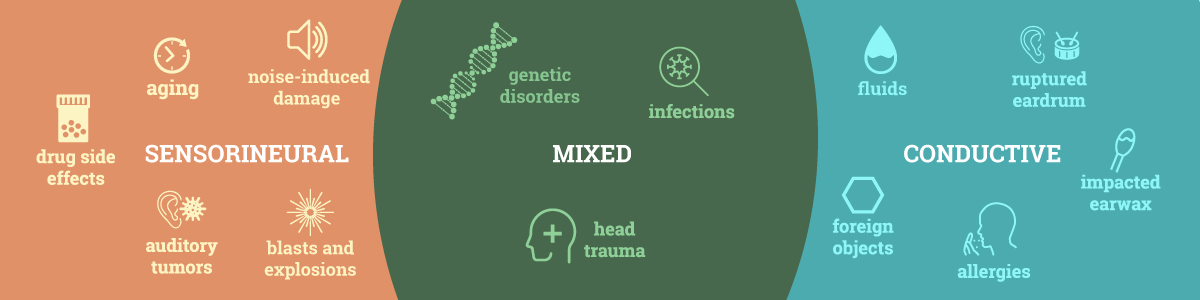

Type of Hearing Loss

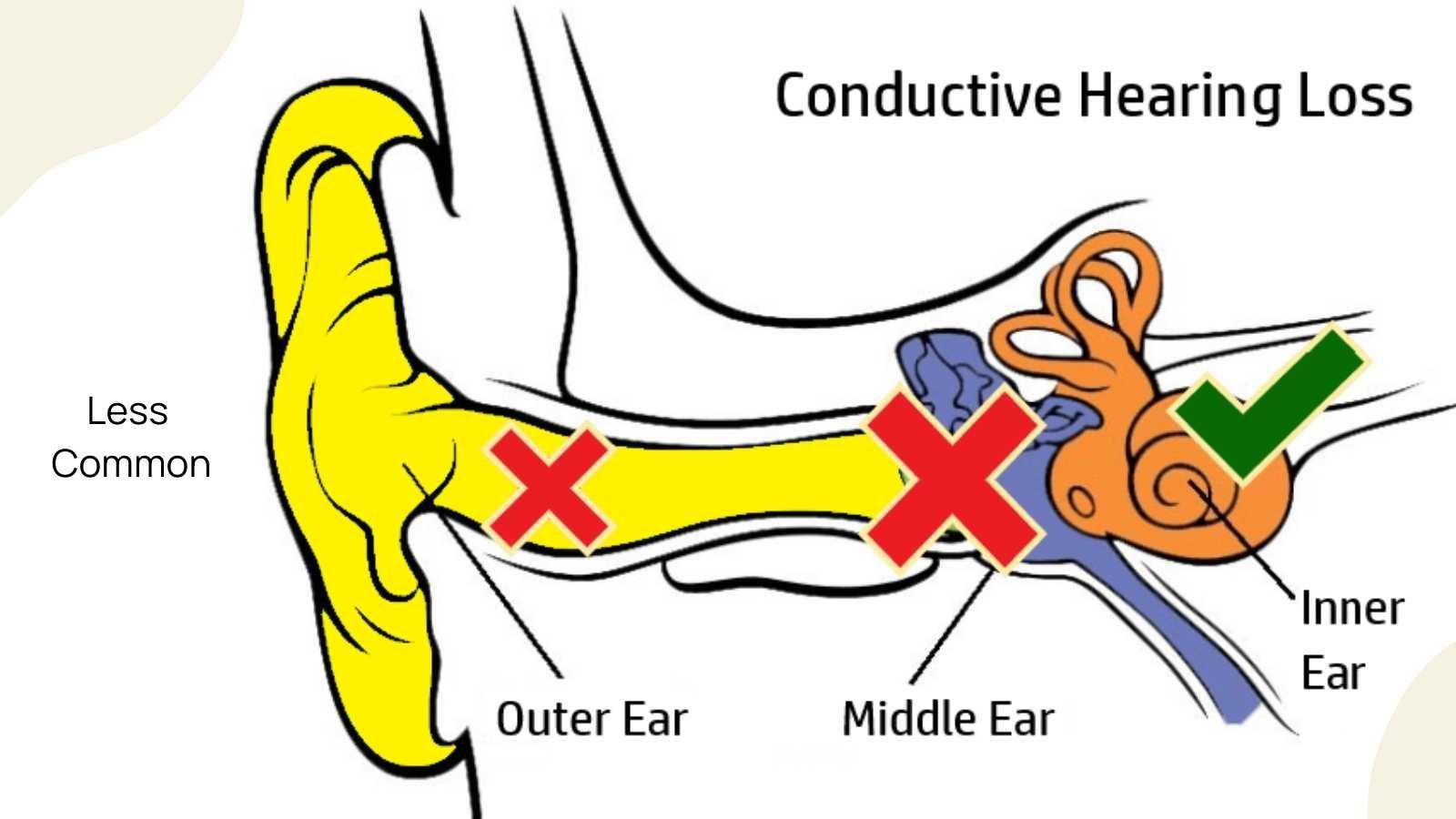

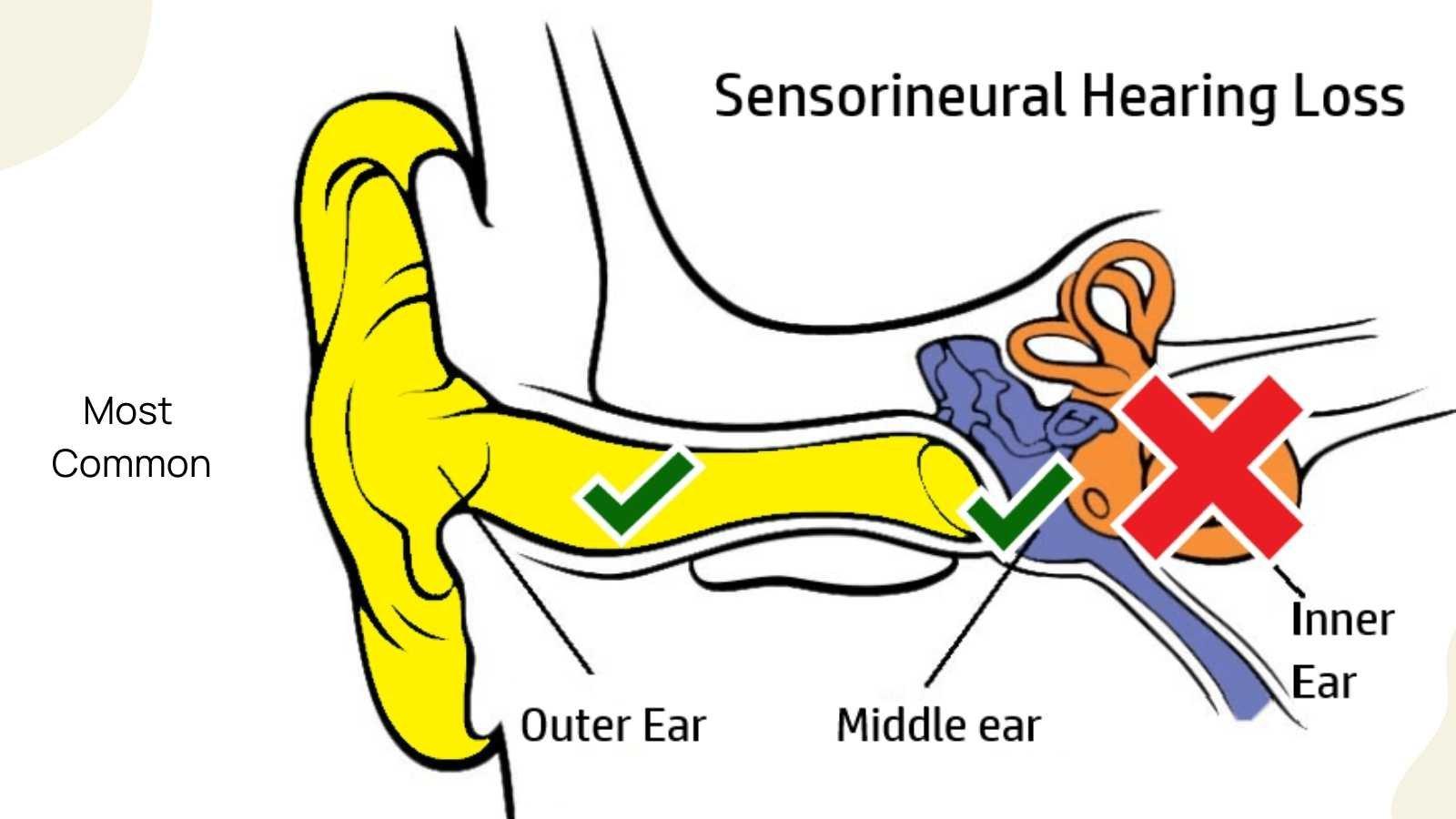

The type of loss may be conductive (damage in the outer or middle ear), sensorineural (hearing loss in the inner ear or nerve of hearing), or mixed (a combination of conductive and sensorineural). Generally, conductive losses are amenable to medical intervention, whereas sensorineural losses are aided primarily through audiologic rehabilitation. One of the main features of sensorineural loss is reduced speech recognition. These three types of loss are the major ones, but there are a few other types. Functional losses have no organic basis and thresholds are often eventually found to be within normal limits. Two other forms of loss with tonal thresholds often within normal limits are auditory processing disorders (APD) and hidden hearing loss. AP disorders arise from the processing centers throughout the auditory system, while hidden hearing loss may be related to damage to the synaptic connections between the inner hair cells and cochlear nerve. In these two types of loss, the symptoms can be subtle.

Auditory Speech Recognition Ability

Auditory speech recognition or identification ability (clarity of hearing) is another important dimension of hearing loss. Discrimination technically implies only the ability involved in a same–different judgment, whereas recognition and identification indicate an ability to repeat or identify the stimulus. Recognition is commonly used by diagnostic audiologists, but identification meshes nicely with the nomenclature of audiological rehabilitation procedures.

Conductive Hearing Loss

Conductive hearing loss is attributed to abnormalities or impairments within the outer and/or middle ear, collectively known as the conductive mechanism. This type of hearing loss results in an abnormal reduction or attenuation of sound as it traverses from the outer ear to the cochlea. Unlike sensorineural hearing loss, which involves irreversible damage to nerve endings, conductive hearing loss can often be addressed through medical or surgical interventions aimed at rectifying the specific issues within the conductive mechanism.

The outer ear's role in collecting, directing, and enhancing sound is crucial for effective hearing. The middle ear, including structures like the tympanic membrane, contributes to the transformation of acoustic energy into mechanical energy, facilitating the transmission of sound waves to the cochlea. When any component of the conductive mechanism is compromised, it hinders the efficient transmission of sound, resulting in a diminished perception of sound intensity. However, the potential for intervention offers hope for individuals with conductive hearing loss, as addressing the underlying causes can lead to significant improvements in hearing capabilities.

Causes of Conductive Hearing Loss

- Foreign bodies in the external ear – Insertion of objects like cotton swabs beads, pencils, erasers, or any foreign object, or insects into the ear canal causing ear pain, itching, and infections. And then try to remove these items, push the earwax deeper, resulting in hearing loss.

- Exostosis – Abnormal formation of the bone on the bone surface in the ear canal.

- Otitis externa – Irritation or infection of the outer ear due to swimming, bacterial infection, allergies, or autoimmune disorder decreases hearing.

- Tumors – Tumors of the nerve that connects the brain usually grow slowly and never spread to anywhere of the brain; creating deafness in the affected ear.

- Abnormal growth of the bone near or in the middle ear – It is known as otosclerosis, troubling in the vibration of the tiny bone which helps to amplify the sound and send them to the brain.

- An unequal pressure in the middle and the external ear – Certainly, it makes the eardrum damage so you may find it difficult to hear anything.

- Ear infections and head colds – Colds and sinus infections can keep fluid trapped in the ear. When this happens, bacteria or viruses can grow and create pus to fill behind the eardrum known as ear infections. It can lead to serious complications.

- Excess ear wax and other fluid build ups – Too much wax and fluids creating a blockage in the ear canal for which sound may not be able to travel to the inner ear.

- Perforated eardrum – A hole in the eardrum. Often it gets better by itself.

Sensorineural Hearing Loss

The inner ear/cochlea is that part of the ear that houses thousands of tiny sensory receptors called hair cells that currently cannot be repaired once they are damaged or destroyed. Thus, injury or pathology in this area causes a sensorineural hearing loss that is permanent. To mitigate the effects of sensorineural hearing loss, hearing aids, cochlear implants, or assistive listening devices are employed. Amplification does not correct damage to the inner ear; rather, sound is amplified and shaped to make auditory information audible to the brain. The only purpose of amplification technologies is to get auditory information through the damaged doorway to the brain.

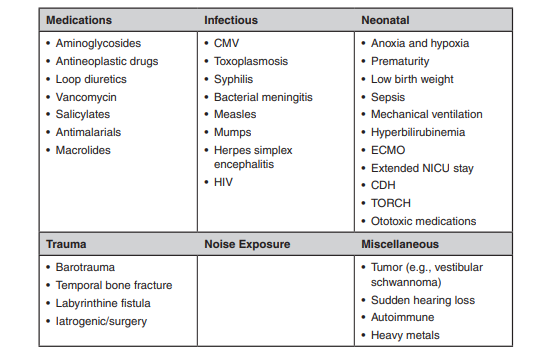

Causes of Sensorineural Hearing Loss

- Ageing – Age-related hearing loss (Presbycusis) occurs as we get older. Health conditions like high blood pressure or diabetes require regular medications that are toxic to the sensory hair cells in the ear.

- Genetics – Around 50% of childhood deafness is genetic. Usher’s syndrome or Pendred syndrome, age-related hearing impairment, and otosclerosis are some examples of hereditary hearing loss causing hearing impairment.

- Side effects of medication – Larger doses of medicine like High BP, heart failure, diabetes, and cancer, etc, are more likely to result in damaging the sensory cells of the cochlea in the inner ear.

- Loud noises (regular exposure) – Creates damage to inner ear structure i.e hair cell swelling and inflammation in the cochlea.

- Head trauma (mild or severe) – It can cause inner ear fluid area rupture or leakage, which can be septic to the inner ear. Only Surgery can help to restore when this happens.

- Tumors – Generally are not curable with surgical removal or irradiation of these benign tumors. If the tumors are small, the hearing may be reversed to 50 percent by tumor removal surgery.

- Otosclerosis – The unusual growth of a small bone in the middle ear. When someone has otosclerosis, one of the bones become unfitted to vibrate freely resulting problem in hearing.

- Ménière’s disease – Abnormal fluid buildup in the inner ear due to allergies, migraines, infections, etc. It usually affects only one year and starts between the age of 20-50.

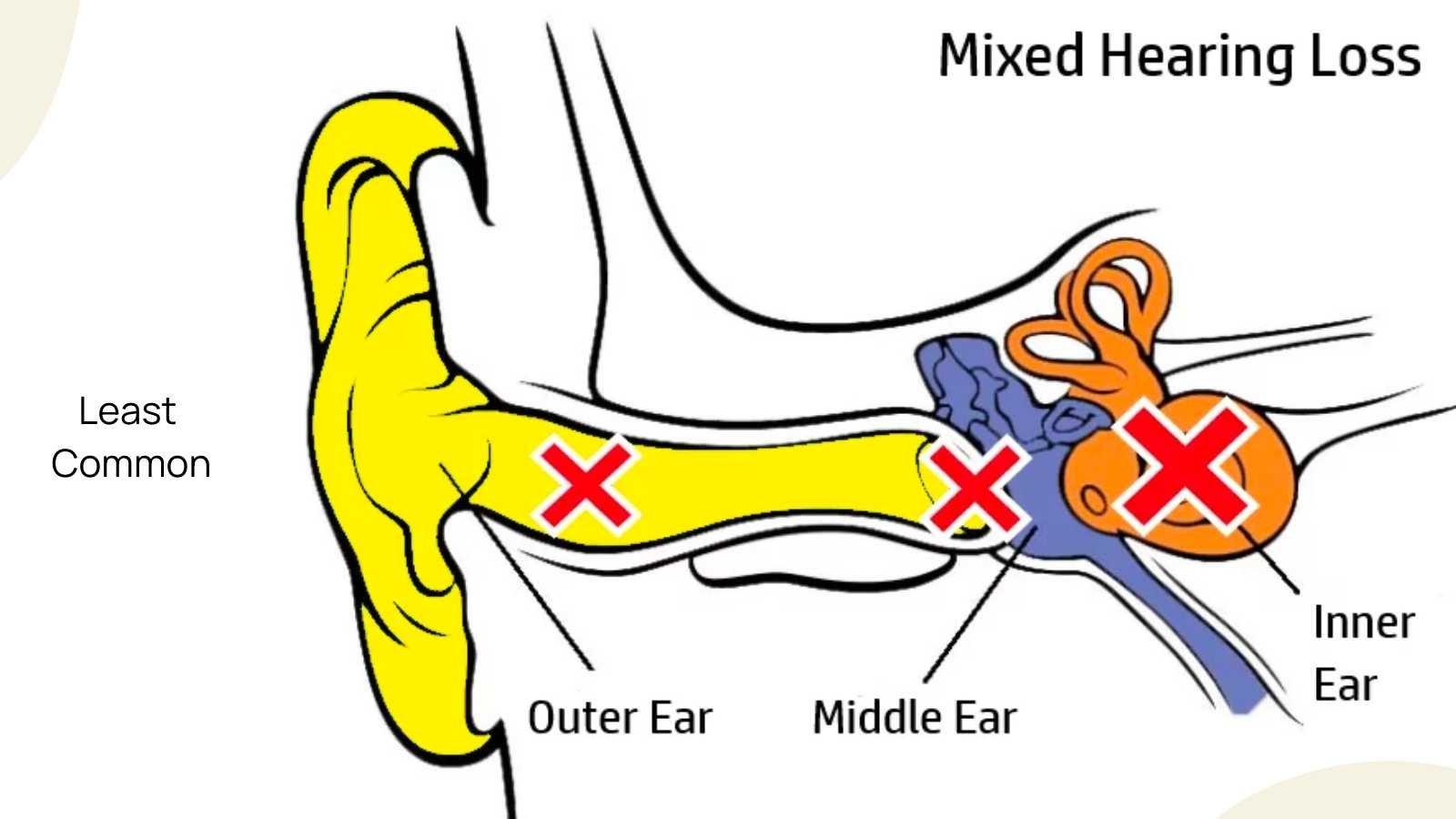

Mixed Hearing Loss

A mixed hearing loss is when two or more ear pathologies, occurring at the same time, cause both conductive and sensorineural hearing losses. For example, a child with a congenital, genetic sensorineural hearing loss could also have ear infections. Another child might have stenotic ear canals blocked by wax, a cholesteatoma (tumor in the middle ear), and a sensorineural hearing loss from anoxia (lack of oxygen at birth). The hearing loss becomes the sum of each individual component, and all pathologies and sites of lesion need to be identified and managed.